Advocacy and Understanding: The Role of Service

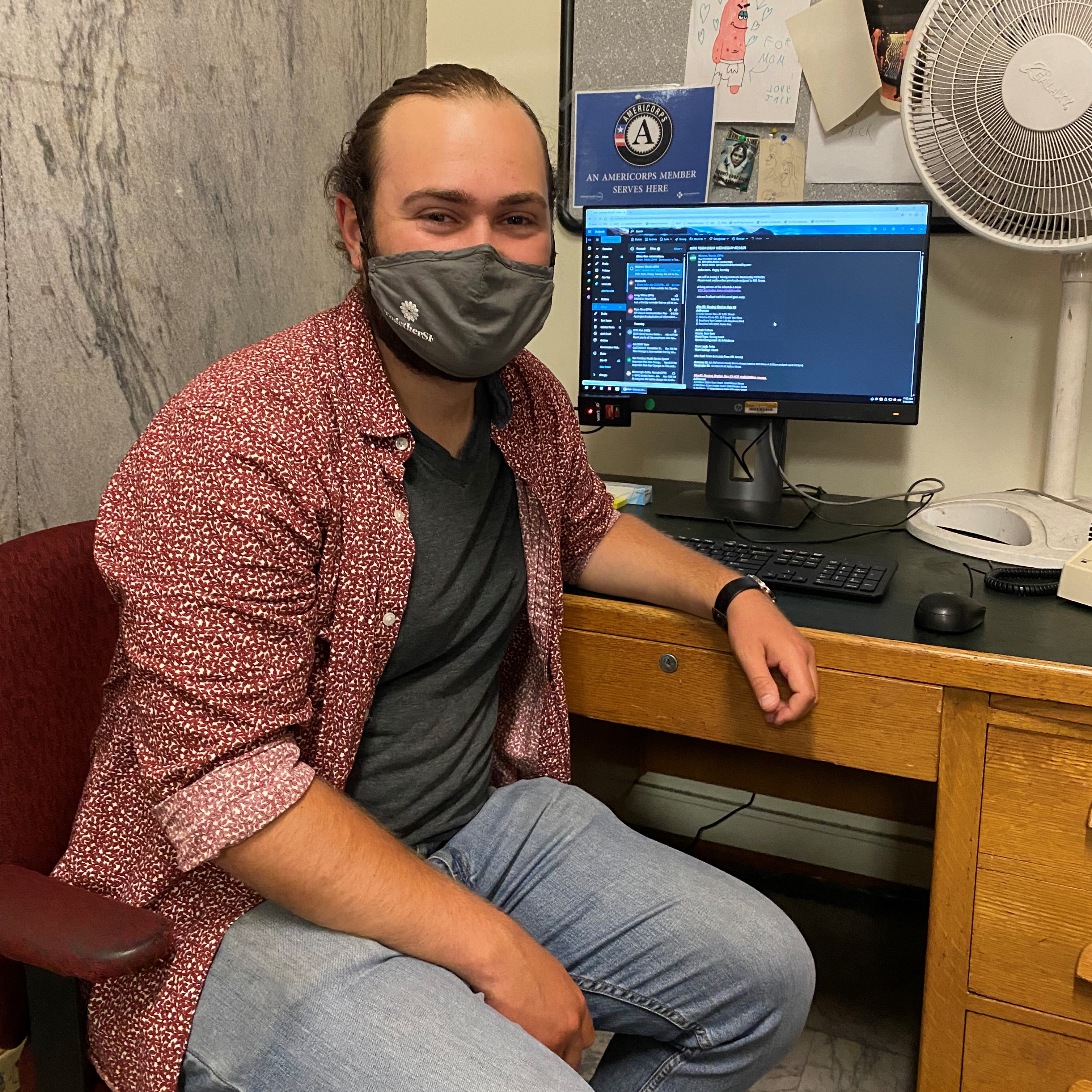

In October of 2020, I began my AmeriCorps service term with the San Francisco Department of Public Health. During the first week of my AmeriCorps service term with the San Francisco Department of Public Health, I notified six of eleven family members living in a two-bedroom apartment that they had tested positive for COVID-19. They, like many other patients, responded that they would be unable to pay rent if they had to quarantine for two weeks. That same week, I tried to get a chronic alcoholic a spot in a detox facility, only to be told they were full and to check back the following week; they were intubated in the ER that evening for acute intoxication. While many of our clients face both acute and chronic health issues, I consistently notice that their most pressing concerns are a lack of food, employment, and housing. These needs are exacerbated by structural racism, with people of color being far more likely to be at risk for food and housing insecurity, and un- or underemployment. By spending time with the clinicians at the Department of Public Health, I became convinced that in order to effectively address health, we must address patients’ social needs, as well as the structural roots of inequity that lead to health disparities.

While notifying patients of their positive COVID-19 results and performing medical education concerning isolation and quarantine, I’ve gotten to know many individuals and families. Although conversations may be as short as fifteen minutes, the opportunity to learn about patients' lives and offer them resources in this extremely difficult time has been eye-opening. These relationships led me to an improved understanding of patients’ ability to follow medical and infectious disease guidelines, and to a better idea of what support they may need. Working with clients in Shelter-in-Place hotels, the trust and rapport we built was fundamental to establishing open dialogue and addressing anxiety over the Covid-19 vaccine, which resulted in many clients being more open to our thoughts and advice. When clients asked if there was a microchip in the vaccine or if they were being used as test subjects, they trusted our counsel and were more likely to get the vaccine.

When treating people living on the street, forming trusting relationships is even more critical. Luckily, when we did street outreach in the Bayview, an underserved neighborhood in San Francisco, our team was led by a doctor who had worked with unhoused people there for three decades. By treating people on the street with deference and humility, we earned their trust, and were then able to perform wound care, to start treatment for substance use disorders, and to dispense common medications without our unsheltered patients having to travel across town to a clinic. These relationships also allowed us to hear about issues facing the unhoused community, whether it be harassment from police, lack of clean water, or fentanyl in the drug supply. Learning about these issues is paramount to improving the health of patients and communities, and so it is critical that the medical system builds this trust. The lasting relationships with the Street Medicine team led our clients to become more involved in support networks, leading to more consistent primary care, and in some cases permanent supportive housing. This experience taught me the importance of meeting people where they are, without judgement, and providing care for people regardless of their circumstances. In my mind, enduring relationships and a patient-centered approach are key to quality patient care, as they allow the primary care provider to advocate for the best possible treatment for their patients, including social supports such as housing, food, and transportation.

This type of advocacy, I believe, extends beyond clinic walls, requiring engagement in public policy and community health to meet the needs of patients and their communities. If the COVID-19 patients I spoke to were able to claim disability payments for the time they had to isolate, they may have been able to avoid infecting others at work. If there had been more detox beds available for my client, they may not have gone back to the emergency room. My term with NHC has taught me that medical teams must develop the close and lasting patient relationships that will allow them not only to treat disease, but also deconstruct the structural inequities and racism that severely limit the effectiveness of even the most advanced medical care. My experience working with COVID-19 patients and unhoused clients has taught me to view a patient as a whole person and has encouraged me to promote structural solutions and policies to improve the health of our communities. As I continue in my career in this field and apply to medical school, I intend to build understanding and supportive relationships with patients, provide the best quality medical care, and advocate for systemic change to address health inequities.